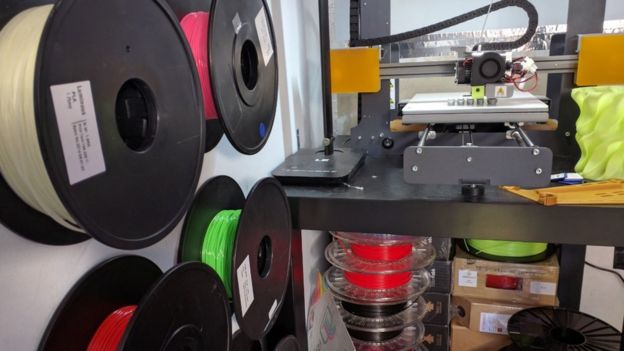

At first glance, the shed, in a back garden in Swansea, doesn’t look remarkable.

Step closer and you’ll hear the whirring of a hard-working machine.

Open the door and, while I’d like to tell you it is Tardis-like inside, it isn’t.

Every inch of space is rammed with equipment, and silver insulation lines the walls.

It’s Mission HQ of an extraordinary duo who call themselves Team Unlimbited – and they are on a self-funded mission to provide free 3D prosthetic hands and arms for children who are born without.

The children get to design their own colours and patterns, and the team – Stephen Davies and Drew Murray – do the rest.

Demand is high, and the shed is full of photos of children from around the world wearing their distinctive design.

Thanks to a blueprint the pair have open-sourced – meaning that anyone with access to a 3D printer, some fishing line and a bit of Velcro, can make one.

Stephen Davies, the owner of the shed, is a CAD (computer-aided design) engineer and father of three. He was himself born without a hand.

It was his own search for a prosthetic that led him to Drew Murray, an IT consultant from Milton Keynes who is part of a volunteer network called e-Nable that makes free 3D prosthetics for children.

Mr Davies says the prosthetic he was offered by the NHS reduced him to tears – and if you look at the photo, you can see why.

In despair he went online, discovered e-Nable and asked Mr Murray, who was the only volunteer based in the UK, to make a hand for him.

It was the first adult hand he had ever created.

“I never thought I would have been able to afford something like that,” Mr Davies said.

“I felt 10ft tall, walking down the road, wearing it. It gave me a huge boost in confidence.

“I was so blown away by that, I knew I had to get involved.”

So the team paired up, and Mr Davies invested hundreds of pounds in two 3D printers and materials.

With the insight of his own experience, they soon created their own design, fixing a few flaws in the existing e-Nable model along the way.

Team Unlimbited was born.

“Everything we do is funded by myself and Stephen and generous donations,” said Mr Murray.

“We are not a charity, we’re just two men in a shed. It’s rewarding to use our professional skills in a different way.”

Stephen Davies’ first recipient was Isabella, who is now nine.

Isabella is very capable with what she calls her own “little arm”, but the prosthetic has made tasks such as learning to play the piano, walking the dog, playing ball with her brother William and turning pages in a book much easier.

Image copyrightAFP

Image copyrightAFP

Her father discovered Team Unlimbited on Facebook, and Isabella chose a pink and purple theme for her first arm.

“The confidence it gave her was amazing,” said her mother, Sarah.

“It stopped her feeling self-conscious. Everyone is different in their own way, but for her this makes her difference a bit more special.”

“It helps me a lot with things I can’t normally do, and things I haven’t tried yet,” said Isabella.

A video of Isabella receiving her first hand has been viewed almost two million times on YouTube and was included by Google in an annual highlights video.

She also appeared in an advertising campaign for the 2016 Paralympics.

She has received three arms so far, and Stephen and Drew’s current template is named after her.

Each hand costs about £30 in materials to make, and takes 12 hours – and the two admit they are swamped with requests.

“I work full time, I’ve got kids, I’ve got a 10-month-old baby; we spend all our evenings and weekends doing this,” said Mr Davies.

“We do it all for free, we don’t even charge postage.”

The design has not been CE-marked, which means it cannot be sold.

Mr Murray says their focus has been on keeping the arm open-source and freely available.

While the device is not as robust as traditional prostheses, which can cost thousands of pounds, children grow quickly and regularly require new ones anyway so they do not necessarily need a long lifespan.

Glyn Heath, senior lecturer in prosthetics and orthotics at Salford University, said 3D printing would not work for all prosthetics, especially lower limbs.

“The materials you can use are limited and the properties of those materials are not necessarily appropriate for taking heavy weights,” he told the BBC.

The cost of traditional prosthetics was high because of the long process of getting them to market, he added.

“It takes a long time to develop prosthetics – they have to be tested to specific medical standards,” he said.

“Not a lot of people use upper limb prosthetics, so the costs of manufacturing are also high relative to the amount you are producing.”

Read more at BBC.co.uk