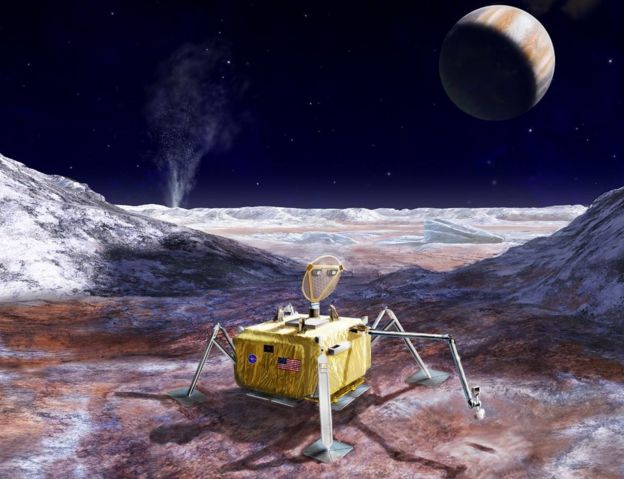

The jovian satellite has a deep subsurface ocean beneath its ice crust and is considered one of the top targets in the search for alien life.

After decades of work, a pair of missions to the moon have been taking shape – and have secured crucial support in Congress.

Scientists hope the lander could be launched some time in the 2020s.

Although Nasa has yet to approve the mission, the agency said it had funding to begin the search for instrument ideas.

Europa: Our best shot at finding alien life?

“The possibility of placing a lander on the surface of this intriguing icy moon, touching and exploring a world that might harbour life is at the heart of the Europa lander mission,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for Nasa’s science mission directorate.

“We want the community to be prepared for this announcement of opportunity, because Nasa recognises the immense amount of work involved in preparing proposals for this potential future exploration.”

Image copyrightNASA/JPL-CALTECH

Image copyrightNASA/JPL-CALTECH

The announcement is intended to provide notice of a two-step competition for experiments. Science teams are expected to put together proposals which would be evaluated by experts working for Nasa.

About 10 proposals could be selected to go forward to the next stage.

Last year, in response to a congressional directive, Nasa outlined its concept for how a landing mission would work.

The report calls for a four-legged lander that would hunt for evidence of microbial life on Europa’s surface. It would touch down with the help of the Sky Crane system used to deliver the Curiosity rover to Mars in 2012, but would use a much longer tether to minimise contamination of the Europan surface with rocket fuel.

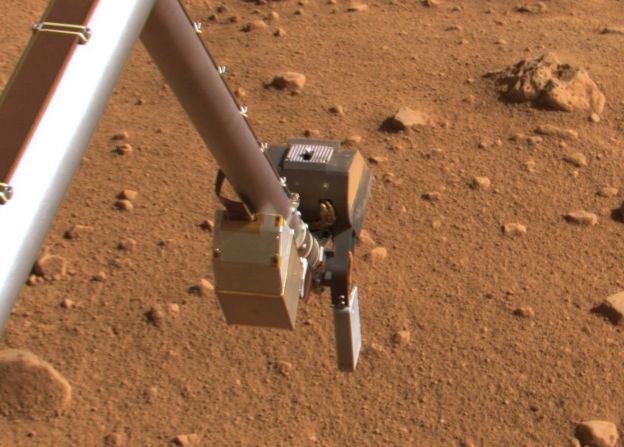

The lander would carry some heritage from Nasa’s Phoenix lander, which touched down in Mars’ “arctic” in May 2008. That mission used a motorised cutting tool called a rasp to break up the hard, icy soil along with a scooper to retrieve the samples for analysis.

The Europa lander will carry a counter-rotating saw in addition to Phoenix’s flight-tested rasp and scoop. Scientists want to dig at least 10cm below the radiation-processed ice, but comparatively little is known about Europa’s surface properties.

Image copyrightNASA

Image copyrightNASA

With temperatures that dip to -170C, however, engineers have to prepare for the eventuality of steel-hard ice that resists Nasa’s best efforts to dig through.

However, scientists believe that if there is any life near the surface, they could detect it at concentrations of at least 100 microbial cells per cubic centimetre of ice. Although Europa’s icy outer shell is thought to be tens of kilometres thick, studying the surface could provide clues to what’s going on deep below.

Warm blobs of ice, or diapirs, could well up from the ocean-ice shell interface, eventually reaching the surface over thousands of years – carrying any evidence of microbial life with them.

Earlier this year, Nasa programme scientist Curt Niebur told me: “The lander is all about hitting the freshest, most pristine sample possible. One way to do that is to dig deep, another way is going to where there is some kind of eruption on the surface – like a plume – that’s dropping very fresh material onto the surface.”

The Hubble telescope has provided tentative evidence for geysers that spew ice out into space from deep beneath Europa’s surface.

The lander would follow several years after a flyby mission called Europa Clipper, which is scheduled to launch in the early 2020s.

Read more at BBC.co.uk