In 1963, a young insurance salesman named Rodney Fox was competing in a spearfishing contest off Aldinga Beach, near Adelaide, South Australia, when he suddenly felt an immense force smash into his side. “I felt like I’d been hit by a train,” Rodney recalls. “My chest was clamped, like in a vice. I was a bone in a dog’s mouth.” At the time, the attack, by a great white shark, was the worst in which the victim had survived. Rodney suffered shattered ribs, a collapsed lung, a ruptured spleen and deep lacerations that arced from his shoulder to his waist. He had a total of 462 stitches and still has a shark tooth embedded in his wrist.

That Rodney lived was miraculous, yet perhaps the most astonishing element of his story is what happened next. To conquer his fear in the aftermath of the attack, he began to study great whites and then, inspired by a trip to Adelaide zoo, came up with the idea of cage diving. Soon, documentary makers and scientists began arriving at his home in the Adelaide suburbs. More people had gone into space than had swum with great whites, and they wanted his expertise to help with their filming expeditions. “It was like having a lot of astronauts at your house,” Rodney’s son Andrew recalls.

Then, in 1973, 10 years after the attack, Rodney received a phone call from Steven Spielberg. The director needed Rodney’s help with a film project – Jaws, which hit the silver screen 40 years ago this month.

Although an oversized mechanical shark was used for close-up scenes in Jaws, live underwater footage was also required, and for that the Universal Pictures production team headed to what is considered the most sharky spot in Australia, the Neptune Islands, a lonely Southern Ocean archipelago 30 miles from Port Lincoln.

The presence of cold water and fur seals means male great whites remain here all year round. When the fur seal pups, which are born on land, take to the water for the first time in May, two-tonne female great whites, up to six metres long, return from months of nomadism.

This is where I have come for my own immersion in shark diving, because of what happened next in Rodney’s amazing story. After playing an important part in the underwater filming for Jaws – locating the sharks, operating cages and advising on how to shoot the sharks to fit the screenplay, working with Australian cinematographers Ron and Valerie Taylor – he then moved into tourism, as a way to educate the public about sharks as well as to earn an income. Rodney Fox Expeditions is now a thriving venture, under the helm of his son Andrew after Rodney retired.

It’s my first day and we are anchored off the North Neptune Islands. For several hours a fishy popsicle of compacted tuna guts has been defrosting on the boat’s dive platform. Gulls whine over the globs of tuna oil and intestine off our stern. Now there are shadows in the water.

At around three metres, the sharks are tiddlers by great white standards – males can grow up to four metres long. Older, larger sharks patrol near the ocean floor. That’s where we’re bound, with our box of “chum” – guts and tuna gills dripping blood. That’s where things might “get hectic”, as Andrew puts it.

Deep-water encounters with great whites are what make Rodney Fox Expeditions the Everest of shark diving. While many of the world’s cage-dive operators hang cages off a boat then lure sharks up to the surface with bait, Rodney Fox takes tourists “out of the kiddie pool” – as Andrew calls it – and down to the depths where great whites live.

With four of us inside, the cage is lowered into the sea where the sharks circle. Cold water creeps up my legs, across my chest, over my face. Fear flutters in my stomach.

Ocean-floor cage-diving is one of those activities that strip you back to yourself. You may be going underwater with a world authority on great whites who has probably notched up more encounters than any other diver over 37 years of cage diving, but as our cage drops through the startlingly azure water I feel alone; I steady my breathing, recheck my air supply, and face my “what ifs”.

It doesn’t matter that every eventuality is covered (spare air tanks; a gap too narrow for a shark to bite; emergency safety floats in case the hoist cable snaps). To hang 25 metres below a boat that now looks like a bath toy on the silvered surface makes me face my suppressed fears. I’m going to have to deal with whatever happens. There’s no escape. Not now we’ve caught the attention of several great whites.

I try, and fail, to push the Jaws theme music from my mind as two white bellies cruise through the splintered sunlight above. Other sharks close around the cage, attracted by the fish-blood that hangs in a rust-red haze around our legs. This is used for scent purposes only (sharks can smell blood 5km away). No meat is fed to the sharks; only fish is used.

Tactics such as these have helped earn Rodney Fox Expeditions a gold star for conservation in an industry which has earned the disapprobation of marine biologists for excessive use of meat for “chumming”. The company also avoids the “crash and bash” of sharks into cages that some operators encourage. “No one thinks it’s OK to poke a lion with a stick through the bars,” Andrew says. “We have a responsibility not to make this a circus act.” Research work is an important element of what the company does, too.

I turn around to see Andrew, camera in hand, leaning far outside the open cage door. Christ, a great white is headed straight at him!

During filming for Jaws, Rodney narrowly dodged snapping teeth to draw “bullet holes” on to a large shark’s snout with lipstick. Another four-metre-long great white became caught in the cage and nearly sank the six-metre vessel that was used for the Orca fishing boat. In Roy Scheider’s famous improvised line, they really did need a bigger boat. The resulting footage of the cage crashing to the seabed was so spectacular Spielberg wrote the incident into his film. Indeed, Spielberg credits Rodney’s role in making Jaws a blockbuster.

There’s no crashing here, but the sharks are close. One cruises past me at eye level, its mouth open to reveal cross-hatched rows of teeth, its snout assessing my electric field. I can see its huge black pupil watching me. You couldn’t pay me enough to leave the cage, but it feels wild, exhilarating, joyous. I barely stop babbling when we resurface.

The qualified divers among our group of 12 passengers on the Princess II, our comfortable liveaboard boat with double and triple en suite cabins, describe this three-night expedition as their trip of a lifetime. Even the non-divers, who remain in surface cages throughout our trip, talk about it as a deeper experience than the shark-watching day trips from Port Lincoln.

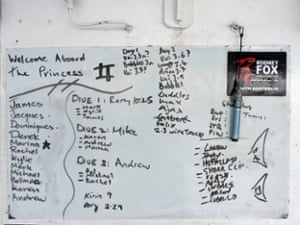

On our first night on board Andrew presents shark photos as though they’re family snapshots. This is Kerry. Here’s Big Ali (“she’s a lovely shark, really smiley”), Big Moo and Cuddles (I’m not making this up: that really was its name). We’re all shark-huggers on this boat, one crew member tells me.

Every night, while the rest of us chow down on dinners of chicken stew or ribs, Andrew pores over the day’s photos to identify old friends and new arrivals for a scientific database. When we leave the Neptunes after 48 hours, there are 20 names are on the dive deck’s whiteboard.

It strikes me on the Princess II that seeing sharks first-hand in the wild may be the best conservation message for the species there is. Yet I can’t help but wonder whether there’s an unspoken element of the appeal of fear too. Maybe secretly that’s why we’re all here. No animal twangs our atavistic nerves like the great white shark. They confront us with what Jaws author Peter Benchley called “the visceral fear of being eaten”. This essential element of the mystique of shark diving is also what helped make Jaws a blockbuster.

So powerful was Spielberg’s film four decades ago that it has made galeophobia – an irrational fear of sharks – the norm even today. Because of Jaws, every shark fatality is global news, even though more people are killed each year by bees. So it seems ironic that the planet’s greatest shark-hugger is partly to blame. Even more ironic is that he survived one of the worst recorded attacks by a great white.

On my final dive I actually enjoy the descent – the vast empty space as we drop underwater, the silence. This time when the sharks circle, I recognise Imax with his kinked tail and Bubbles with his bloated belly. I’m struck by the sharks’ brilliant hydrodynamics, their streamlined bodies. And look at the colours: gun-metal grey, burnished steel, a dark bronze sheen. I’ve become a shark-hugger.

It feels a privilege to hang here above the kelp and witness such a powerful, perfectly evolved predator in its own environment. If only Spielberg had included their strange beauty in Jaws too.

• The trip was provided by South Australia Tourism. Rodney Fox Expeditions runs two- to five-night shark diving trips out of Port Lincoln from AU$1,195pp. Flights were provided by Singapore Airways , which flies to Adelaide from Heathrow and Manchester from £930 return

Cage diving tips from the Shark Trust

Cage diving is the most exciting way to see large sharks at close quarters. South Africa is regarded as the world cage-diving capital, but cage-diving operations are widespread – including some in the UK.

This can be a contentious form of shark ecotourism: stories abound of unscrupulous charter boats toying with sharks, encouraging “mouth-gaping” and publicising sharks as “man-eaters”. These are easily avoided with online research. Generally those that promote conservation, science and education are more likely to offer encounters which are respectful and beneficial to humans and sharks.

There are five key steps to consider when booking a shark cage dive:

• Do a little online research prior to selecting an operator.

• Ask to view the operator’s code of conduct.

• Only dive with those operators who use chum as a scent trail, to draw sharks in. Avoid operators who attract sharks through feeding (using chunks of meat), which some believe could modify the natural behaviour of sharks.

• Look for operators with an education programme, covering sharks’ life history and role in ecology, threats from humans, and diving conduct.

• Charter vessels should never disturb sharks – or any other marine animal – engaged in natural feeding or courting behaviour.

John Richardson, conservation officer, sharktrust.org

Read more:https://www.theguardian.com